Premium Report

Getting Started as a War Room Trader

Bryan Bottarelli, Head Trade TacticianWelcome to Monument Traders Alliance. This is the premier investing community of experts, novices and everything in between.

And being a novice won’t stand between you and wealth. All you need is a few lessons in the basics to start trading like a pro.

Consider this your manual to options and one of our most fundamental strategies in The War Room.

In this report, we’ll quickly look at the strategies and timelines for trading in The War Room. Then I’ll teach you all about the “Scaled Selling Technique.” It’s my method to extracting every bit of profit out of every single position – all while limiting your risk.

Then I’ll introduce you to your new best friends, the Greeks.

Finally, I’ll leave you with a glossary of options trading terms. This will be invaluable as you embark on your trading journey.

Now let’s begin!

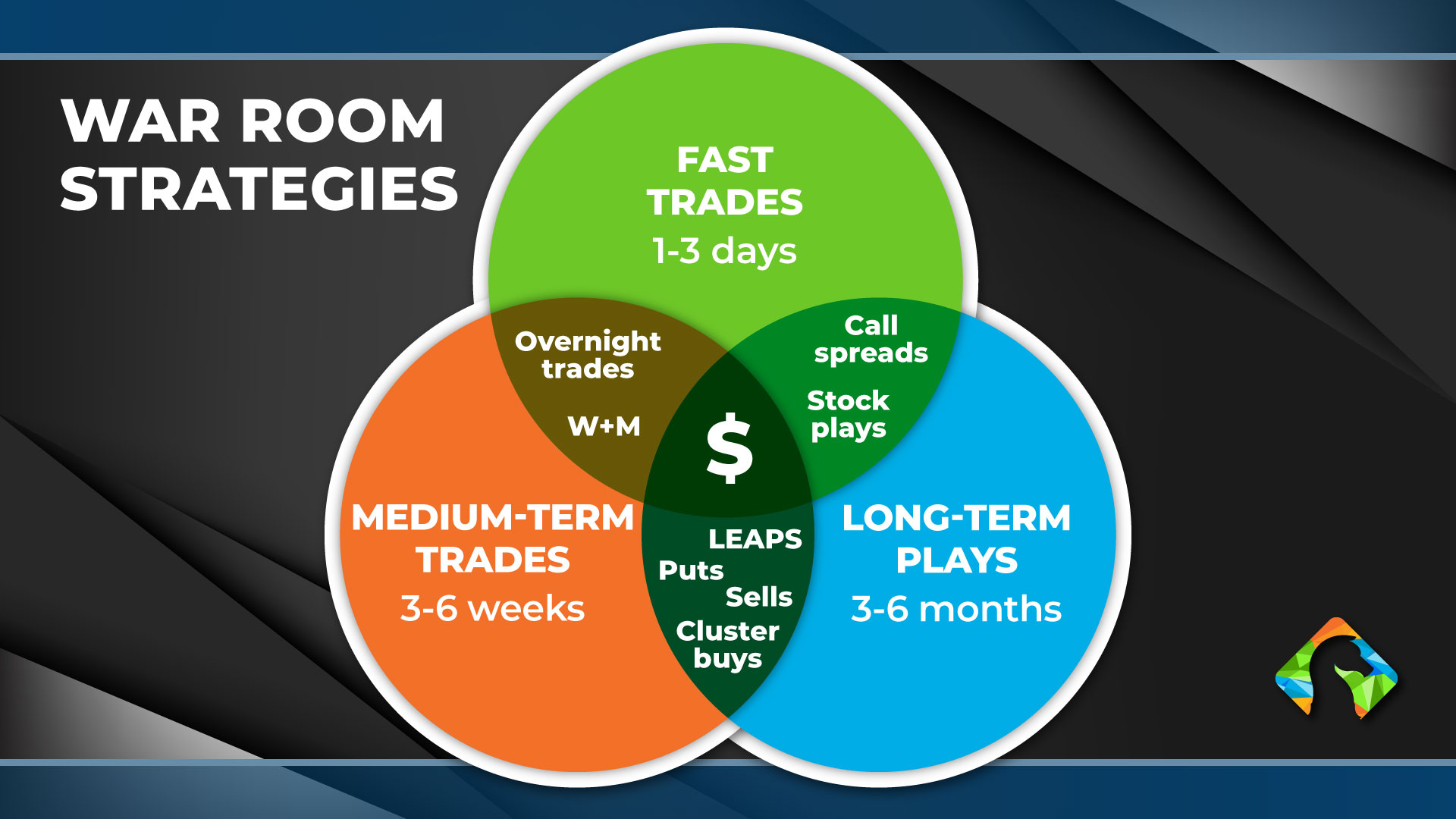

Trading Timelines

Fast Trades: From 15 minutes to a week.

Medium-Term Trades: 3-6 weeks.

Long-Term Trades: 3-6 months.

Secrets of the Scaled Selling Technique

Investors of all kinds ask the same question: When should I sell?

Finding a consistent answer to this question is nearly impossible. That’s why this report is key…

The methods of the Scaled Selling Technique offer you an answer to this impossible question. These methods also allow you to lock in huge returns without the risk of holding too long or second-guessing your exit points. This technique reduces risk and eliminates greed.

It sounds too good to be true. But it’s actually pretty simple. As long as you follow the guidelines in this report, you’ll find success.

The entire philosophy behind the Scaled Selling Technique involves selling off small segments of your position at predetermined performance targets.

For example, let’s say you invest $3,000 into company XYZ’s January 2021 calls for $100 each. It’s a total of 30 contracts.

By using the Scaled Selling Technique, you always sell half of your position the moment it reaches a 50% return.

In our example, you’d sell 15 contracts when you make a 50% gain overall. That way, you’d lock in a $2,250 profit.

Then, if your remaining 15 contracts go on to reach a 100% return, you always sell one more or one-quarter of your remaining position. In this case, you would sell four contracts, roughly 25% of your position, leaving you with 11 contracts.

That would net you an additional $800, with each of those additional contracts worth $200 when you sold them.

Moving up the profit scale, if your remaining contracts hit 200%, sell another 25% of your position, or three of your remaining 11 contracts, leaving you with eight. Each of those contracts would be worth $300 for a total of $900.

Continuing up the scale. If your remaining eight contracts hit 300%, sell another two of them, 25% of eight. That’s an additional $800.

If your final six contracts go on to reach 400%, sell them at $500 and bring in an additional $3,000. With your position closed, you’d have turned your $3,000 into $7,750.

That’s a 158% gain on your overall position!

With six remaining contracts, you could have kept going even longer. But in this example, we played it safe and closed out at 400%.

Here’s a chart of the exit targets for reference.

- Sell half of your entire position at 50%.

- Sell one additional contract (or 25% of your remaining position) at 100%.

- Sell one additional contract (or 25% of your remaining position) at 200%.

- Sell one additional contract (or 25% of your remaining position) at 300%.

- Sell one additional contract (or 25% of your remaining position) at 400%.

But what if your gains stall out?

For example, say you lock in your gains at the 50% mark and sell one contract at the 100% gain mark, but then prices begin to reverse and move lower.

That’s when you implement Plan B. You lock in profits on all of your positions if they re-test a predetermined profit target…

In this scenario, you sell half your position for 50% and then one contract for 100%. But then the remainder of your position drops back down to the 50% level. In that case, you would close out the remainder of your position at 50% and lock in your gains.

The entire Scaled Selling Technique is a way of testing just how much profit you can squeeze out of every position. It comes complete with a back-up plan to exit the whole position for gains the moment your maximum profits have been achieved.

Sure, executing the Scaled Selling Technique means paying more transaction fees. But in my experience, these additional costs are a worthwhile investment for the profit margins that can be achieved with this methodology.

I will guide you on all of these exit points with regular updates on my positions.

You can certainly feel free to manage your positions however you see fit, but the Scaled Selling Technique can serve as a backbone for determining exit points.

Knowing your exit targets for every play ahead of time gives you an unprecedented advantage over 90% of other traders and investors. Advantages like these are what ensure successful wealth creation!

Armed with this straightforward system of profit taking, you’ll put yourself in the best possible position to maximize your returns on each and every trade in The War Room.

You’re now equipped with a sound trading strategy. To take your trading even further, here are the Greeks.

The Greeks

Pro traders often describe risk involved in an options position using letters of the Greek alphabet. These are called the Greeks.

Properly understanding the relationship between your position and the Greeks can have a profound effect on your trading success. Here are basic definitions of the Greeks.

Δ (Delta): The relationship between the option’s price and the price of the underlying asset. It’s the price sensitivity of the option. Delta is the change in option price relative to a change in the price of its underlying asset.

Γ (Gamma): The rate of change of delta. It illustrates how much the price of the option changes when the price of the underlying asset changes.

Θ (Theta): The rate of change between an option and time. It is the decrease in an option’s value over time.

ϒ (Vega): The rate of change between an option’s value and the underlying asset’s volatility. It’s the option’s sensitivity to volatility.

Still with me? Now it’s time to look at some examples to see what the Greeks look like in action.

There are four basic positions we can have as options traders: long calls, long puts, short calls and short puts. Let’s take a look at each one, see what our Greeks are and then how they change depending on how long we have until expiration.

| Long Call | Short Call | Long Put | Short Put | |

| Delta | Long | Short | Short | Long |

| Gamma | Long | Short | Long | Short |

| Theta | Short | Long | Short | Long |

| Vega | Long | Short | Long | Short |

A few observations…

Long calls and short puts have the same delta. This makes sense because if we’re long a call, we want the stock to go up. If we’re short a put, we don’t want the stock to go down. Either way, we make money when the stock rises.

Gamma and vega are always the same direction. Think about being long a straddle. Our Greeks for this position are long gamma, short theta and long vega. (Our delta will be very close to zero because we are long both a call and a put). In this situation, we make money in one of two ways. Either the stock makes a big move and our long call or long put increases in value or implied volatility rises, thus increasing the value of both our calls and puts.

We know how much money we stand to gain through this volatility increase by looking at our vega. In a situation where the stock starts moving, we’ll make money as our delta increases in the direction of the movement. Whether the stock rises or falls, we know how long or short we are for each $1 move by looking at the size of our gamma. In both cases, we’re looking for movement in order to make money, so that’s why we are long gamma and vega.

Theta is always the opposite direction of gamma and vega. In our long straddle example, we make money when the stock moves a lot or when volatility increases. Theta is negative because it’s denoting the amount of money we’re paying every day for the privilege of waiting for a big stock move or a volatility spike.

For our purposes in The War Room, the most important Greek for us will be delta. The genius of this ever-changing delta reading is that it carries multiple uses and definitions. We’ll discuss these various valuation metrics and meanings below.

Delta Meaning No. 1: Percent Chance of Expiring in the Money

Every stock option has a delta that ranges between 1 and 99. This number denotes the chances of the option expiring in the money.

At-the-money options will have deltas very close to 50. That means that if you own an option with a $30 strike price and your underlying stock currently trades right at $30 a share, then your option has a 50% chance of expiring in the money.

As you can imagine, options that are in the money carry higher deltas, while out-of-the-money options have lower deltas.

The delta reading of an option can change drastically. It all depends on how long it has until expiration and the volatility of the stock.

Understanding the relationship between delta and various time measures can tell you a lot about how floor traders expect various stocks to trade.

Delta Meaning No. 2: Measure of Directional Risk

In addition to telling you the percent chance of your option expiring in the money, delta is also used to measure directional risk.

For this example, let’s use Proctor & Gamble (NYSE: PG). Say you bought 10 PG January 80 calls. In this case, pro traders would say you’re now long 453 deltas.

Math: 10 PG options multiplied by a delta reading of 45.31 = 453.

This tells you that for every $1 move in Proctor & Gamble’s stock price, you can expect to gain (or lose) $453. As a call owner, a $1 move up would make you $453 on your 10 positions, while a $1 move down would lose you $453. Delta allows you to know this risk versus reward ahead of time.

The use of delta comes in handy when you have more positions open. For instance, say you want to hedge your 10 long PG January 80 calls by selling 10 of the PG January 82.50 calls. This call sale would result in a short delta of 351.

Math: Selling 10 PG January 82.50 calls multiplied by a delta reading of 35.06 = 351.

At this point, you can combine your two delta positions and see that your total delta for the position is long 102.

Math: Long 453 deltas from your 10 PG January 80 calls plus short 351 deltas from selling 10 PG January 82.50 Calls: 453 + -351 = Long 102.

With your newly adjusted hedge position, you know that for every $1 move in PG stock, you can expect to make (or lose) $102. As you can see, you’ve lowered your risk by managing your long and short delta positions.

Put deltas work the same way as call deltas, but in the opposite direction. For example, if you are long calls, you’re also “long delta.” If you’re long puts, you’re said to be “short delta.” This simply refers to the direction in which you want the underlying stock to move to make you money.

By keeping a running tally of your total delta risk, you can remain properly hedged. Doing so also gives you a clear idea of your profit or loss for every $1 that your underlying stock moves. This will help you remain profitable during all market conditions.

Learning to calculate deltas will greatly improve your trading results, both in terms of income generation and loss prevention.

As you begin receiving our trading alerts, you’ll get a better understanding of the relationship between delta and your open positions. In doing so, you’ll begin to understand a lifelong wealth-building skill that’s used by the top pro traders.

Finally, I have a glossary of important options trading terms for you to reference on your journey to becoming a trading pro in The War Room.

The Options Glossary

The purpose of this glossary is to familiarize yourself with the professional terms around options trading. That way you can understand the thought behind every trade in The War Room. It will also help you understand how pro traders communicate.

Most importantly, familiarizing yourself with these terms can help you make the most money from your new membership.

BREAKEVEN PRICE: The price that an underlying instrument must reach in order to produce intrinsic value in the option equal to the buyer’s cost of initiating the position. Calculating the breakeven price helps you make an intelligent decision about whether to buy the option.

BULL MARKET: A prolonged increase in investment and market prices. An investor is “bullish” if they think an asset’s value will increase.

CALL: An option (agreement) that gives the option buyer the right to buy an investment at a set price within a specific amount of time. Note: The call option buyer is not obligated to execute the option.

CASH ACCOUNT: Your securities account with a brokerage firm that you use to pay for your purchases in full.

CLOSE: To exit the options market. When you sell an option, you are selling back to the market, telling your broker to resell it “to close.”

COMMISSIONS: Fees that brokers charge investors when buying and selling options and other investments. Many brokers have special deals on volume trades – if you can arrange it.

COVERED CALL: A call where the writer already owns the stocks that he may find himself obligated to sell.

DAY TRADING: Buying and selling investments within the same day. When the market closes, a day trader doesn’t have any open positions.

ETF: An exchange-traded fund (ETF) is a group of stocks or various investments.

EXERCISE: The act of buying or selling the underlying optioned material. You would not exercise an option unless it were a winning position.

EXPIRATION: The last day an option can be exercised or offset. Make sure you know the exact expiration date of any option you purchase. Once an option has expired, it no longer conveys any rights and, in effect, ceases to exist.

EXTRINSIC VALUE: The worth of the premium, represented by time and volatility as opposed to the option’s real, or intrinsic, value.

FLOAT: The number of publicly traded shares that are available.

FORM 4: The form that company insiders must file with the SEC when they buy or sell shares of the company in which they are designated as insiders.

FUNDAMENTAL ANALYSIS: A way to evaluate an investment’s value by assessing related economic and financial factors.

HEDGE: Any maneuver to protect capital or profits, either by buying or selling the underlying item or by using an option or derivative.

HOLD: Continuing to hold what you have with whatever stops have been noted, while not selling off the position or adding to it.

IN-THE-MONEY OPTION: An option with intrinsic value. An in-the-money call option has a strike price below the current price of the underlying instrument. An in-the-money put option has a strike price above the price of the underlying instrument.

INTRINSIC VALUE: The portion of the premium representing real value. An option has intrinsic value if the difference between the market price and strike price would make the option profitable if exercised.

LAND MINE: A completely unforeseen event that moves a particular trade against you.

LEAPS: Long-Term Equity Anticipation Securities that can run up to three years in time. They are traded on various options exchanges and include stocks, stock indexes and other instruments traded on those exchanges. In effect, a LEAPS call is a substitute for the actual shares of stock during its life – if it is “in the money.” If it is “out of the money,” a LEAPS call may be considered a cautious way to control the price of a rising stock with limited risk over a very long time.

LIMIT ORDER: A buy order to purchase an option at or below a specified price or a sell order to sell an option at or above a certain price. Use limit orders to minimize risk, but be aware there is no guarantee your option can be bought at the desired price.

LIQUIDITY: The degree to which an investment can be bought or sold quickly. Higher trading volume tends to make an investment more liquid.

LOCK IN: Protecting gains. This can be accomplished with a trailing stop or by buying a protective, out-of-the-money option to act as a hedge and keep the door open to further profits if the trend continues.

LONG: Buying an investment and hoping to sell at a higher price down the road.

MARGIN: This allows investors to borrow money to leverage their investment strategies.

MARGIN ACCOUNTS: Good-faith deposits investors make to their broker when borrowing from the broker to buy securities and futures. Buying on margin exposes you to unlimited risk.

MARKET MAKERS: Traders responsible for improving investment liquidity by facilitating buy and sell orders.

MARKET CAP: The company’s total market value (stock price multiplied by number of shares outstanding).

MARKET ORDER: An order to buy or sell an option at the market price, synonymous with telling your broker to “do his best” as quickly as possible. Using a market order means you have no control over your entrance or exit price, making your risk uncertain.

NAKED CALL: The opposite of a covered call, where the writer does not own the shares they may become obligated to sell. Instead, the call is written against a cash deposit in a margin account.

OFFSET: Closing out a position in a previously purchased option by selling it in an offsetting transaction prior to expiration. This is done by exercising an option and immediately putting the just-acquired security back on the market, either by selling stocks gained from exercising a call or buying stocks sold in a put. This immediately captures the option’s intrinsic value and locks in profits.

OPTION: A financial instrument giving an investor the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a specific investment at a set price for a predetermined amount of time.

OUT-OF-THE-MONEY OPTION: An option with no intrinsic value. That is, if you exercised the option, you would lose money on the difference between the market price and strike price.

PAPER TRADE: Tracking options daily on paper, without actually investing any money in them. This is a good way to learn about premium movements as they relate to the underlying stock or future without risking any capital. Once you’ve paper traded for a while, you’ll be ready to start investing.

PREMARKET: Trading activity before the market opens.

PREMIUM: The price you pay to open a put or a call. The premium is the sum of an option’s intrinsic value and time value. Premiums are arrived at in the open competition of buyers and sellers.

PUT SELLING: Selling options to collect income while simultaneously obligating yourself to buy the underlying shares if they close at or below the strike price at or before expiration.

PUT: An option (agreement) that gives the option buyer the right to sell an investment at a set price within a specific amount of time. Note: The put option buyer isn’t obligated to execute the option.

QQQ: The Nasdaq-100 Index is commonly referred to as QQQ. It allows investors to buy a share of stock to invest in the most actively traded companies on the Nasdaq.

RESELL: The act of selling an already bought option back into the marketplace, thus closing the position. Use the term “resell” so brokers will not make the mistake of selling (writing) an option in the subscriber’s “open,” instead of “closed,” account.

RESISTANCE: A price level that is difficult for an asset to exceed due to increased selling pressure.

RISK-TO-REWARD RATIO: The amount of money at risk compared with the potential return.

SERIES: The range of strike prices available for an option.

SHARES OUTSTANDING: The total number of shares a company has issued.

SHORT SELLING: Borrowing an investment, selling it and hoping the price drops so the investment can be repurchased for a lower price and then returned to the investment lender.

SNIPER SELL: A term we coined to represent our automatic, no-questions-asked sell price. For example, we may recommend an option for $2 and set a sniper sell at $4. In this example, let’s say news is released around lunchtime that pushes the option up to $4, but you don’t see an alert advising you to sell. In this case, do not wait. With the sniper sell already in place, you know to take your profits and sell. Overall, this move is a safeguard that works in your favor and allows you to maximize profits on any quick moves.

SPREAD: The difference between the bid price and ask price.

SUPPORT: A price level that’s hard to go below due to increased buying pressure.

SUPER-LEVERAGE: The art of using other people’s money to try to profit while maintaining limited risk at all times. The purchase of put and call options is one form of super-leverage.

SWING TRADING: Holding an investment position overnight or up to a few weeks before exiting the position.

STOP LOSS ORDER: An order to close a position at a certain price if the market turns against you. A stop loss order becomes a market order if the price of the item hits the stop limit.

STRIKE PRICE: The price at which the option gives you the right, or obligates you, to buy or sell the underlying shares.

TECHNICAL ANALYSIS: Predicting an investment’s price movements by assessing market price movements, patterns and trends.

TRADING HALT: When a stock halts trading for dissemination of potentially market-moving news.

TRAILING STOP: A stop loss order that automatically goes higher as an option moves up in price. This can lock in greater profits if the market reverses, but be aware that sometimes profitable trades may reverse, triggering the trailing stop, and then resume their upward move.

TREND: The direction of an investment’s price movement, such as an uptrend or downtrend.

UNDERLYING INSTRUMENT: The investment instrument an option gives you the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell. The current price of the underlying instrument directly relates to the cost of the option, or its premium.

VOLATILITY: The fluctuation in market price of the underlying security. Volatility can be a key factor in an option’s premium.

VOLUME: The number of shares that trade over a set time period.

WRITER: An individual who sells calls and puts. The writer has an obligation to sell the stock (in the case of a call) or buy it (in the case of a put) if the buyer decides to exercise the option. All the money an options writer will make is known at the time the option is written: It consists of the premium received from the buyer, less the commission the writer pays his broker.